Marin Weaver

(202) 205-3461

marin.weaver@usitc.gov

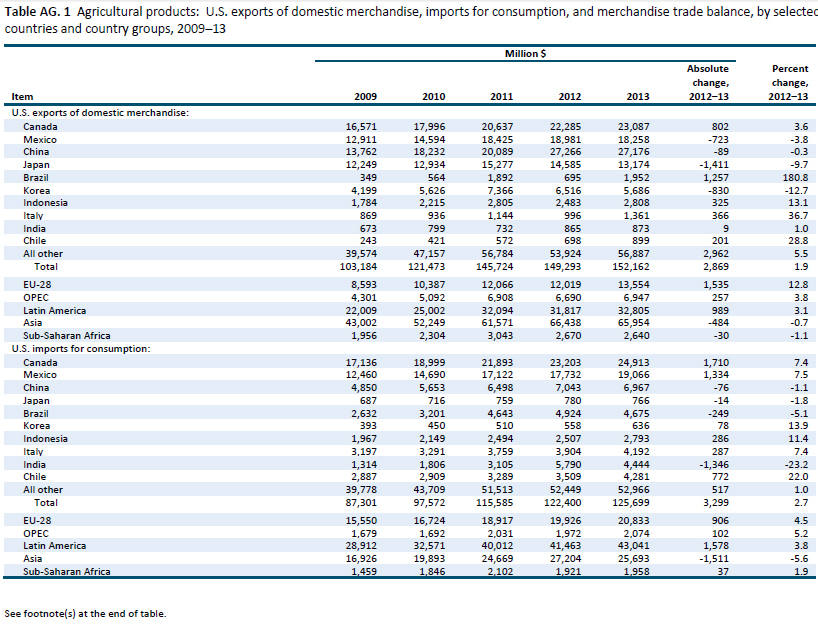

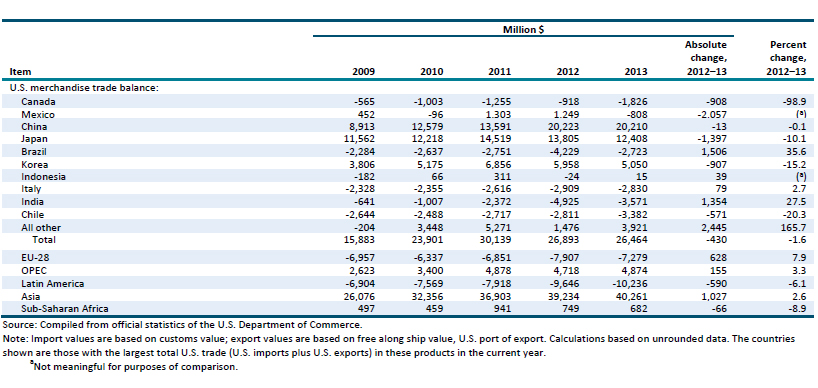

Change in 2013 from 2012:

- U.S. trade surplus: Decreased by $430 million (2 percent) to $26.5 billion

- U.S. exports: Increased by $2.9 billion (2 percent) to $152.2 billion

- U.S. imports: Increased by $3.3 billion (3 percent) to $125.7 billion

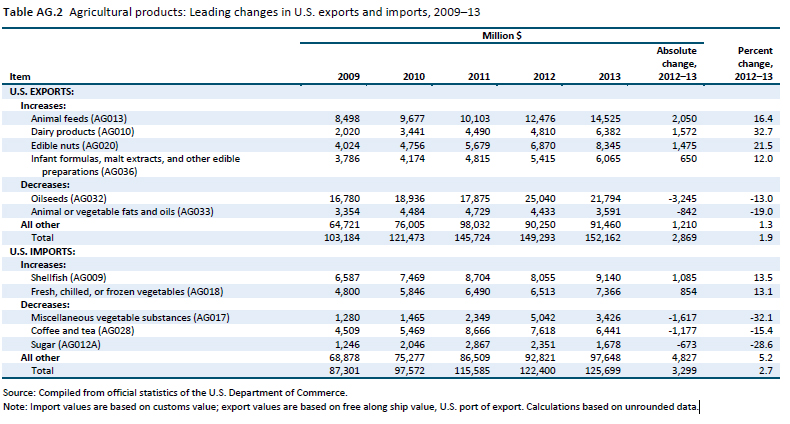

The U.S. trade surplus in agricultural products fell by 2 percent to $26.5 billion in 2013, as an increase in U.S. agricultural exports was offset by somewhat higher growth in imports (table AG.1). Three commodity groups led the growth in U.S. exports—animal feed, dairy products, and edible nuts, all of which had annual export increases in excess of $1 billion. Income growth in developing countries drove the increased demand for these products. However, these gains were partially offset by decreased exports in other commodities, especially the $3.3 billion dollar decline in oilseed exports.

The picture was similarly mixed in terms of U.S. imports. In particular, a 13 percent increase in the value of shellfish imports, driven by higher shrimp prices, was a major contributor to the growth in the value of U.S. agricultural imports. This growth was somewhat offset by declines, due to lower prices, in the value of imports in two commodity groups—miscellaneous vegetable substances (e.g., guar gum, pectins, and seaweed) and coffee and tea.

Leading export markets for U.S. agricultural products in 2013 were the same as in 2012—China, Canada, Mexico, and Japan. Exports to China were flat, while exports to Canada increased slightly (4 percent). Exports to Mexico and Japan declined by 4 percent and 10 percent, respectively. In 2013, the United States was a net importer from both Canada and Mexico, historically its leading suppliers of imported agricultural products. U.S. imports from both countries increased by more than 7 percent in 2013, reflecting in part increased imports of wheat from Canada and sugar from Mexico.

U.S. Exports

Increases in U.S. agricultural exports in 2013 were led by animal feed, dairy products, and edible nuts (table AG.2). Animal feed exports increased by 16 percent to $14.5 billion. This commodity group covers a wide range of products, but the two largest for U.S. producers were “soybean oilcake and other solids” and “brewing/distilling dregs and waste.” These two products together accounted for almost 50 percent of all animal feed exports in 2013 and were major contributors to the increase in exports in this group. Most of the growth in exports was driven by increasing demand for animal feed in China, Vietnam, and Turkey. As incomes rise in these developing countries, consumer demand grows for animal protein, which in turn increases demand for animal feed.

U.S. dairy exports have also increased significantly in recent years. Nearly 80 percent of the year-over-year $1.6 billion increase in U.S. dairy exports came from four products—skim milk powder (also known as nonfat dry milk), cheese, whey and whey products, and butter. The fastest-growing export markets for U.S. dairy products are in Asia and North Africa. Rising global demand, especially in rapidly developing economies, increased both export prices and volumes for U.S. dairy products in 2013.

U.S. exports of edible nuts rose by 22 percent to $8.3 billion in 2013.69 The 28 members of the European Union (EU-28) and Hong Kong are the biggest markets for U.S. exports; in-shell almonds and in-shell pistachios account for the largest share of exports to these partners. The biggest absolute growth in U.S. exports of nuts came from shelled almonds (up $708 million) and was largely caused by higher prices. Prices of these tree nuts have generally risen along with global demand because supply is constrained. Nut trees are limited to specific climate zones and often require many years to reach their full production capacity. Many factors contribute to the growth of demand (manifested in consumer willingness to pay higher prices) for tree nuts, including consumer perception that nuts are a healthy snack, rising demand in developing countries, and nuts’ status as a gift or special snack for holidays in some Asian markets.

By contrast, U.S. oilseed exports fell by $3.2 billion, the largest absolute decline of any U.S. agricultural product in 2013. Soybean exports, which make up about three-quarters of U.S. oilseed exports, fell 13 percent by value and 8 percent by quantity. When U.S. prices reached near-record highs in the summer of 2013, importing countries switched to Brazil, which had a large supply of soybeans due to a bountiful harvest. U.S. oilseed exports declined in almost every market. Exports to China showed the largest decline in absolute terms, falling $1.6 billion (11 percent) from 2012.

In 2013, U.S. agricultural exports to Brazil rose sharply, increasing 181 percent to almost $2.0 billion, about two-thirds of which was wheat. The value of wheat exports increased from $13 million in 2012 to $1.2 billion in 2013, a 30-year high. Brazil’s traditional supplier, Argentina, experienced its worst wheat harvest in a century and was unable to meet Brazilian demand due to a ban on wheat exports imposed by the Argentine government. As a result, Brazil lowered its tariff on U.S. wheat from 10 percent to zero during April–December 2013, which made it less costly to import U.S. product. These circumstances created an opportunity for U.S. exporters, who benefited from record U.S. wheat production in 2013.

In 2013, U.S. agricultural exports to Japan fell more in absolute terms ($1.4 billion) than those to any other market. This was driven by a $1.2 billion (41 percent) fall in corn exports, primarily because of a 38 percent decline in feed corn volumes. Japan’s global feed corn imports fell about 15 percent by value and 10 percent by volume as it substituted some corn with lower-priced sorghum and wheat in animal feed. In addition, since late 2012, Brazilian feed corn has had a price advantage over U.S. feed corn; in 2013, average Japanese import values for this commodity from Brazil were $309 per metric ton, compared to $341 from the United States. As a result of this price discrepancy, Japan’s imports from the United States fell more sharply than the average, and Brazil replaced the United States as Japan’s largest feed corn supplier.

U.S. Imports

Shellfish led the increase in the value of U.S. agricultural imports in 2013, accounting for about one-third of the total increase in value. In 2013, U.S. imports of shellfish grew by 14 percent to $9.1 billion. Two-thirds of this growth can be attributed to a 26 percent increase in the value of imports of certain shrimp and prawns. Prices rose as shrimp production fell in major producing regions of East and Southeast Asia, a result of an outbreak of early mortality syndrome (EMS) disease starting in late 2012.

The United States has large agricultural trade flows (imports and exports) with its North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) partners, Canada and Mexico, but was a net importer in this category from these two countries in 2013. U.S. imports from both Canada and Mexico reached their highest levels ever in 2013, at $24.9 billion and $19.1 billion, respectively. Mexico and Canada benefit from their proximity to the United States, which gives them logistical advantages over other U.S. import suppliers, and from preferential trade access under NAFTA.

In 2013, the largest absolute increase in U.S. agricultural imports from Canada were of live cattle (not for breeding), which grew 22 percent to $1.3 billion, and wheat (non-durum), which grew 37 percent to $779 million. Both increases were driven by higher import quantities, although prices also increased. A major factor contributing to increased U.S. imports of Canadian cattle was the closure of a beef slaughter plant in Quebec, resulting in higher volumes of Canadian cattle delivered for slaughter in the United States. In addition, low prices in late 2012 caused some U.S. producers to wait until 2013 to deliver cattle for slaughter, and a slaughter plant in Alberta closed for a week, causing a temporary increase in cattle shipments to the United States. The United States imported more Canadian wheat in 2013 because some U.S.-produced wheat was diverted to Brazil (see above). Canada was able to make up the shortfall in the U.S. market because of a good harvest and limited competition from other producing regions like Australia, which had lower production levels in 2013 than the year before.

The U.S. agricultural imports from Mexico with the largest absolute increases in 2013 from 2012 levels were raw cane sugar and avocados. The value of U.S. imports of raw cane sugar rose by $314 million to $415 million; the import quantity increased sevenfold.85 U.S. refiners can import Mexican sugar duty free and quota free under NAFTA. U.S. imports of Mexican avocados grew by $230 million to $992 million in 2013 because of both higher prices and increased quantities shipped. Rising demand (both globally and within the United States) and the timing of Mexico’s shipments, which led to tighter supplies in the U.S. market late in the year compared to 2012, forced U.S. import prices for avocados higher in 2013. In addition, U.S. per capita consumption of avocados more than doubled between 2010–13 because of multiple factors, including a promotional campaign by the U.S. industry and avocados’ wider availability at restaurants.

U.S. imports of miscellaneous vegetable substances in 2013 fell by $1.6 billion (32 percent) from 2012. About half of these were mucilages and thickeners derived from guar seeds, also known as guar gum. Imports of guar gum fell by $1.8 billion (52 percent), largely because of lower prices rather than lower imported volumes. Guar gum is used in oil and shale gas exploration, and as a thickener in certain processed foods. The vast majority of guar gum is imported from India (97 percent in 2013). In 2012, guar gum prices were high because fears of production shortages in India, which accounts for about 80 percent of global guar gum production, drove a speculative bubble. In 2013, prices fell because (1) the Indian government, which had banned guar gum futures trading between March 2012 and May 14, 2013, issued guidelines aimed at reducing speculation on guar gum, and (2) guar gum production in India increased as farmers devoted more acreage to guar seed.

The value of U.S. imports of coffee and tea fell by 15 percent to $6.4 billion. This decline was primarily the result of lower prices for certain Arabica coffee imports, which fell 23 percent ($956 million) by value in spite of a 5 percent (40,379 metric tons) rise in quantity. Lower prices drove down the value of U.S. imports of Arabica coffee from almost every supplier, and five suppliers had declines of over $100 million each—Brazil ($209 million), Guatemala ($146 million), Indonesia ($124 million), Honduras ($117 million), and Mexico ($106 million).

Arabica coffee prices fell because of a large harvest in Brazil for the second year in a row, as well as higher production in Colombia after a successful replanting program beginning in 2010.