ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES

ESTIMATED

TARIFF EQUIVALENTS OF SERVICES NTMS

Lionel Fontagné

Cristina Mitaritonna

José E. Signoret

Working Paper 2016-07-A

U.S. INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION

500 E Street SW

Washington, DC 20436

July 2016

Office

of Economics working papers are the result of ongoing professional research of

USITC Staff and are solely meant to represent the opinions and professional

research of individual authors. These papers are not meant to represent in any

way the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its

individual Commissioners. Working papers are circulated to promote the active

exchange of ideas between USITC Staff and recognized experts outside the USITC

and to promote professional development of Office Staff by encouraging outside

professional critique of staff research.

Estimated Tariff Equivalents of Services NTMs

Lionel Fontagné, Cristina Mitaritonna, and José E. Signoret

Office of Economics Working Paper 2016-07-A

July 2016

Lionel Fontagné

Paris School of Economics University Paris 1

Centre d’Études Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (CEPII)

Cristina Mitaritonna

Centre d’Études Prospectives et d’Informations

Internationales (CEPII)

José E. Signoret

U.S. International Trade Commission, Office of

Economics

Jose.Signoret@usitc.gov

1. Introduction

As previous trade liberalizations have lowered tariffs

worldwide, nontariff measures, or NTMs, remain as the most visible issues to be

addressed. This is especially true in the case of services, where measures

likely to affect services trade do not involve tariffs. In fact, significant

trade agreements currently under negotiation, such as a number of mega-regional

free trade agreements and an ambitious multilateral Trade in Services Agreement

(TISA), particularly aim at reducing services NTMs. The result is that there is

wide interest from both policy makers and economists in understanding the

impact of these measures.

Unfortunately, quantifying the restrictiveness of NTMs

for services has proven to be difficult. The main limitation has been the lack

of comprehensive data, whether trade, policy, or microeconomic data.

Gathering data on actual policies has been especially

challenging. Up until recently, information on the regulatory environment

affecting services trade was not available for a wide range of countries, nor

was it necessarily collected in a consistent fashion. Efforts by the World Bank

(Borchert, Gootiiz, and Mattoo, 2012) and the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Geloso Grosso et al., 2015) to collect

this information and to develop services trade restrictiveness indexes as “summary

statistics” of the level of restraints have been an important advance. By

themselves, however, these indexes (often called STRIs) have no obvious

economic meaning, and they would require some empirical analysis to associate

them with trade costs.

One strand of the literature has used the STRI

information to explain the observed international variation in price-cost

margins, conditional on other firms and country factors. The pioneering work of

Dee (2004) and Dihel and Sheperd (2007) provide early examples of this work.

Fontagné and Mitaritonna (2013) conduct a similar analysis and stress the

limitations of this approach. First, qualitative information must be

arbitrarily transformed into a quantitative measure of the restrictiveness of

each measure considered individually. Second, this approach is very

data-consuming with respect to both microeconomic evidence and the determinants

of price-cost margins in services sectors. As a consequence, estimated

coefficients on restrictiveness indexes have to be used out of sample. This is

a huge restriction, because the distribution of firms or markups within a given

sector necessarily diverges across countrieseven more

so when countries at different levels of development are considered.

Jafari and Tarr (2015) nevertheless employ this

method, using the World Bank STRI, to compute ad valorem equivalents (AVEs) for

a large set of countries. Other recent research using STRI information has

relied on gravity modeling. The analyses by van der Marel and Shepherd (2013) and

Riker (2014) using the World Bank index, or by Nordås and Rouzet (2015) using

the OECD STRI, are examples of gravity models that incorporate STRI values in

their econometric specifications. Finally, Gooris and Mitaritonna (2015)

exploit the ordinal nature of restrictiveness levels to assess the trade impact

of a measure in place in a given country for a given sector. They conclude that

the trade-impeding effects of restrictions may be nonlinear.

Although available for a large set of countries, data

on services trade flows are much more aggregated than data on merchandise

trade. But even if information on trade in services is limited, it is possible

to use it to compute AVEs of the effects of barriers to trade in services on

the quantities (instead of the prices) of traded services. Of course, bilateral

trade data are not available for all possible trading partners, and the

existing gaps have to be filled via estimation methods with reconstructed data.

Sources of such data may include the services trade data in the Global Trade

Analysis Project (GTAP) and other global databases.

Fontagné, Guillin, and Mitaritonna (2011) illustrate

how to carry out such an analysis and then compare the results obtained with

different identification strategies and different datasets. Their analysis uses

a reduced form of the gravity approach to estimate services trade without

relying on STRI information. The tariff equivalents are then inferred by

comparing the inward multilateral resistance term for each country with that of

a benchmark country. In this note, we build on this approach and provide AVEs

of restrictions on trade in services for 117 countries in 2011. This estimation

uses GTAP data, making it consistent with modeling efforts by several trade

economists.

The econometric estimation used is this note is a

practical approach that can be applied to obtain AVEs even for services sectors

that do not line up with STRI sectors and for years for which there is no STRI

information. It also bypasses the need for data on price-cost margins within

sectors and countries. In fact, as in this note, estimates across many

countries and sectors can be updated as more recent trade data become

available. Further, this approach is not susceptible to how regulations are

scored and how these scores are then weighted in forming the STRI.

Our results compare with those of Fontagné, Guillin,

and Mitaritonna (2011), who used GTAP data for the year 2004. We use the same

method, although the set of countries for which we have estimated the equivalents

is larger. For the sake of comparison, we also provide results obtained with

Fontagné, Guillin, and Mitaritonna’s original sample of countries, but for 2007

and 2011. In the latter case, we estimate and compute AVEs on the reduced

sample of 64 countries.

The reader, however, must be aware that the estimated

AVEs are only rough estimates of the restrictiveness of regulations on

services. Our approach is likely to pick up trade cost factors beyond policy

restraints, so that the tariff equivalent results may reflect a broad range of

“frictions.” And although these estimates can easily be incorporated into

large-scale trade models, they are not likely to be fully actionable. Berden et

al. (2009), for instance, consider that, overall, 50 percent of NTM AVEs in

goods and services in transatlantic trade may be actionableand even

that 50 percent is probably an ambitious goal. Evidence on this question has to

be taken from trade negotiators or specialists in the concerned sectors, and it

is beyond the scope of this note. Notice, however, that we systematically

benchmark our estimations against a country with a zero AVE, although

regulations on services may be present in this country. We are not measuring

the cost of regulations, but rather their restrictiveness for trade flows.

The rest of this note is organized as follows. Section

2 presents the empirical approach used. Section 3 describes the data and

econometric identification. Results are presented in section 4. The last

section concludes the discussion. The full set of updated results is included

with this note as an Excel file.

2. Empirical Framework

Many methodological issues can arise when using the

gravity approach to construct AVEs of barriers to trade in services. First, the

distribution of residuals of the estimated equation is sensitive to problems of

specification and omitted variables, which affects the estimation of tariff

equivalents. Hence it may be preferable to rely on a strategy based on country

fixed effects. Second, an assumption must be made on the elasticity of

substitution used to transform the parameter estimates to AVEs. The value of

the equivalents is highly sensitive to this assumption, although the ranking of

the restrictiveness of countries’ regulations in a given sector is not. These constraints

led us to choose a simple identification strategy in tackling unobserved

dimensions (like restrictiveness) in the importing country. Fontagné, Guillin,

and Mitaritonna (2011) show that identifying the quantity effect of barriers to

trade in services by relying on the GTAP database provides highly usable

measurements of AVEs. We have built on this approach.

Our first step is to estimate a gravity equation in a

cross-section relying on partially reconstructed data. In the GTAP database on

trade in services for 2011, based on OECD data, the gaps for missing data are

filled and then the database reconciled. There are accordingly two issues here:

we rely on a very specific set of data as regards trade in services, namely the

GTAP dataset of trade in services, while deriving estimates only with

cross-sectional methods. These issues are not major obstacles, however, as

illustrated by Fontagné, Guillin, and Mitaritonna (2011): while the latter

study used alternative data sources and a panel database, the results were

shown to be not too different.

3. Data and identification

We make use of a relative small set of data sources.

The main source of data used in this paper remains the GTAP database, which

provides bilateral trade in services for 15 services sectors for the year 2011:

air transport (atp), communications (cmn), construction (cns), dwellings (dwe),

electricity (ely), gas distribution (gdt), insurance (isr), other business

services (obs), other financial intermediation (ofi), other government services

(osg), other transport (otp), recreational services (ros), trade (trd), water

(wtr), and water transport (wtp). This dataset has more countries than the GTAP

database for the year 2004 that was used in Fontagné, Guillin, and Mitaritonna

(2011). For sake of comparison, we provide tariff equivalents computed using

alternatively the (reduced) sample of countries found in Fontagné, Guillin, and

Mitaritonna (2011) and the enlarged sample of countries available in the GTAP

database for the year 2011. For sake of comparison with Fontagné, Guillin, and

Mitaritonna (2011), we keep the decomposition into the following services

sectors: cmn, cns, obs, trn, trd, isr, ofi, and osg. In this listing, trn stands

for transport, which includes the three transport sectors (atp, wtp, and otp).

As in the reference article, wtp is also kept separately.

The gravity variables were obtained from the Centre

d’Études Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales (CEPII) and updated for

as necessary using data obtained from the World Bank.

For each services sector, the estimating equation used

in the current analysis takes the form:

(1)

Where represents the log of exports from

country to partner .

Trade costs other than regulations between and are proxied by ,

the log of their bilateral distance. The vector contains bilateral trade determinants

common in the gravity literature, including distance, contiguity, a colonial

relationship, a common language, engagement in a free trade agreement, etc.,

here controlled by dummy variables. We include exporter and importer fixed effects to estimate the usual

multilateral resistance terms. Since we do not have time series, gross domestic

products (GDPs) should collapse in these fixed effects. However, we would like

to clean the importer fixed effect from the importer GDP, in order to capture

only the degree of restrictiveness of trade in this importing country. We

constrain the coefficient for expenditures in the importing country to 0.8, to

normalize exports by the potential size of the market.

The last term represents an error term.

The last step involves the derivation of the tariff

equivalents. There are two ways to compute the average protection applied by

each importer: either from the estimated residuals (as in Park 2002), or else

from the importer fixed effect coefficients. Although the importer fixed effect

coefficient captures something larger than the protection itself, it is

preferable to residuals. Not only do the latter contain mixed information other

than protection, but their magnitude and goodness largely depend on the fit of

the equation performed.

We need to examine the underlying theory in more depth

to understand the assumptions involved in relying on the canonical gravity

equation derived by Anderson and van Wincoop (2003) in order to compute the

revealed trade barriers of country .

Exports from country to country accounting for a share of world income can be expressed as a simple

function of the product of their GDP and of trade costs.

Noting as GDP (subscript for world), trade costs (the power of the AVE) and the elasticity of substitution, we

have the following expression for the bilateral trade flows :

(2)

Where refers to the price index of the demand

function in and to a term which transmits the effect of

an increase in the level of import restrictiveness for non-j services importers that

stimulates exports from i to j:

(3)

How the estimated equation fits in is

simple. In our model (equation 1), is observed, is captured by the exporter fixed effect,

by the importer fixed effect, and is in the constant.

We must now assume that the regulation on a services

sector in j has the same impact on

exports for all affected partners i,

hence and that the impact on of changes in is small enough to be neglected, as a result

of a small enough (the weight of the destination country

expenditure in j over the world

production).

As regulations cannot be directly observed, one should

compare the actual trade with a theoretical situation (subscript free), excluding any trade costs

associated with restrictive regulations on trade in services in the destination

j,

hence computing the theoretical ratio of ,

which after simplification is equal to ,

with .

If we assume that and are similar, then the term can be omitted.

As the theoretical value cannot be observed either, there is a need to

define a benchmark country, supposed to be the free trader of the sample. The

benchmark is the country with the highest positive difference between the

actual and predicted average import values. All calculations must be made

relative to this benchmark, and one must normalize the ratio of actual to

predicted trade for each importing country by the same ratio computed for the

benchmark. Under the assumptions made above and after summation over j’s partners, the log of this double

ratio therefore becomes the difference in the logs, as follows:

(4)

Where is the highest importer fixed effect

coefficient.

From equation 1 we get the estimation of ,

however the specific values of the tariff equivalents ( ) will also depend on the elasticity of

substitution that is not estimated in the model, but needs

to be assumed.

Following Fontagné, Guillin, and Mitaritonna (2011)

and for sake of comparison, we use the assumption that .

A higher provides lower AVEs, and vice versa. The

relative ranking among the different countries, however, is not sensitive to

the assumed value of the elasticity of substitution.

4. Results

We now show the results of the estimated

equations using data for 2011 and the largest set of countries (117) and for

nine sectors of services, disregarding water, electricity, gas manufacture

and distribution, recreational and other services, and dwellings.

As noted, air transport and other transport are not considered

separately, but included in all transports (trn), a category that also includes

water transport. Distance has a negative impact on trade in services, because

distance is a proxy of many other dimensions besides transport costs (e.g.,

communication costs). Contiguity and a colonial relationship facilitate trade

in services, because of the existence of business networks and the fact that

certain services (such as construction) are provided cross border. The

liberalization of trade in services in Europe shows up in the positive

coefficient for Europe, and the same conclusion holds for NAFTA,

notwithstanding the lower integration in North America. Again, business

services and the presence of affiliates of foreign companies may play a role

here. What is observed in Europe or North America contrasts sharply with the

observed parameter estimate for Latin America.

Most important for us, however, are the

importing country fixed effects, as explained above. We now rely on these fixed

effects to compute the AVEs, using an elasticity of substitution of 5.6.

Results are shown in table 2 for the top five more open countries and the top

five more protective ones, for each category of services. We report in

parentheses in table 2 also the fixed effect of the best performer, so that the

estimated AVEs in 2011 can be recalculated using different elasticities of

substitutions.

An Excel file with the complete set of

results for the 9 sectors and the 117 countries is available with this note.

This file does not report results for a limited number of pairs (sector,

importer), as the parameter estimates were not significant. This set of unreported

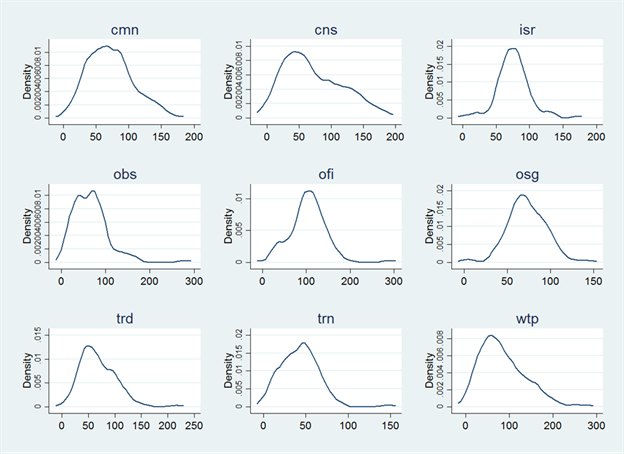

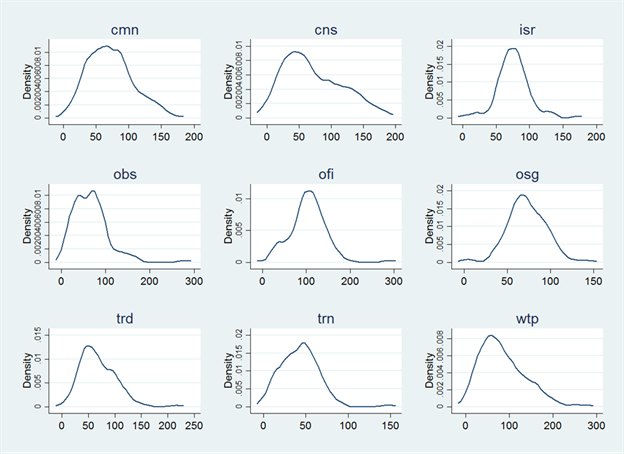

pairs corresponds to 7.7 percent of the total number of pairs. In figure 1 we

show the distribution of estimated AVEs by services sector for the remaining

92.3 percent of the sector-importer pairs.

For the sake of comparison with Fontagné,

Guillin, and Mitaritonna (2011), who computed AVEs for 64 countries in 2004, we

perform the same calculation for 2007 and 2011, restricting our estimation of

parameters and derivation of tariff equivalents to these 64 countries. Results

are provided in the Excel file.

Table

2

Top five free traders and restrictive importers of services, ad valorem

equivalent, percent, by sector, 2011

|

Sector

|

Top 5 more open countries, by sector

|

|

Top 5 more restrictive countries, by sector

|

|

cmn

|

LUX

|

DNK

|

BEL

|

SGP

|

GBR

|

|

BGD

|

PRY

|

NAM

|

BRA

|

TTO

|

|

0.0 (2.121)

|

15.1

|

17.3

|

19.0

|

19.5

|

|

140.6

|

143.4

|

147.5

|

148.9

|

172.3

|

|

obs

|

IRL

|

LUX

|

SGP

|

MLT

|

BEL

|

|

ECU

|

MEX

|

PRY

|

BFA

|

LAO

|

|

0.0 (1.769)

|

8.4

|

11.8

|

15.2

|

16.3

|

|

153.6

|

155.5

|

157.8

|

170.7

|

280.1

|

|

trn

|

SGP

|

HKG

|

GRC

|

DEU

|

GBR

|

|

BFA

|

BGD

|

NAM

|

ZMB

|

LAO

|

|

0.0(1.223)

|

0.4

|

6.6

|

7.3

|

9.1

|

|

79.3

|

84.2

|

85.0

|

85.5

|

148.0

|

|

wtp

|

GRC

|

NOR

|

SGP

|

HKG

|

ISR

|

|

BFA

|

PRY

|

ZMB

|

BGD

|

LAO

|

|

0.0(3.667)

|

7.6

|

11.3

|

16.8

|

20.1

|

|

186.3

|

192.2

|

194.4

|

228.2

|

275.1

|

|

cns

|

AZE

|

SAU

|

ZMB

|

LUX

|

MYS

|

|

BFA

|

BRA

|

PRY

|

BGD

|

TTO

|

|

0.0(2.815)

|

0.5

|

6.8

|

7.7

|

12.8

|

|

161.4

|

170.6

|

173.5

|

180.5

|

180.6

|

|

isr

|

IRL

|

LUX

|

DNK

|

SGP

|

MEX

|

|

MOZ

|

RWA

|

LAO

|

BLR

|

TTO

|

|

0.0(1.569)

|

10.8

|

23.0

|

23.9

|

26.5

|

|

124.8

|

130.0

|

131.8

|

135.6

|

170.8

|

|

ofi

|

LUX

|

IRL

|

HKG

|

TWN

|

MLT

|

|

ZMB

|

GIN

|

BGD

|

TTO

|

LAO

|

|

0.0(2.292)

|

24.3

|

31.9

|

33.6

|

34.3

|

|

165.8

|

170.9

|

174.7

|

196.4

|

290.6

|

|

trd

|

IRL

|

SGP

|

LUX

|

HKG

|

NLD

|

|

GIN

|

TGO

|

BGD

|

ZMB

|

LAO

|

|

0.0(2.454)

|

13.5

|

17.8

|

21.6

|

25.9

|

|

126.4

|

131.0

|

147.9

|

151.3

|

217.5

|

|

osg

|

SAU

|

KWT

|

BRN

|

MDG

|

UKR

|

|

ZMB

|

IND

|

ETH

|

TGO

|

LAO

|

|

0.0(1.212)

|

8.9

|

35.2

|

35.6

|

38.3

|

|

107.6

|

112.9

|

119.5

|

129.3

|

146.3

|

Note: Numbers in parentheses are

estimated fixed effects for the benchmark countries.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Figure

1

Kernel density of AVEs estimated for 117 countries and 9 services sectors, ad

valorem equivalent, 2011

Source: Authors' calculations.

5. Conclusion

This note derives a set of AVEs of restrictions on

cross-border trade in services for 118 countries and 9 sectors, using the GTAP

database. The trade data refers to 2011. These equivalents are derived from a

quantity method using a gravity model of trade. The econometric estimation is

performed sector by sector and the reported AVEs in this note and in the

accompanying dataset are based on an assumption of common elasticity of

substitution across sectors. Based on the econometric estimation and the

elasticity assumption, AVEs for frictions affecting cross-border services trade

are large in many sectors. It should be noticed, however, that only a fraction

of these estimated costs are reasonably subject to policy changes (or

“actionable”) in most circumstances.

References

Anderson, James E., and Eric van Wincoop. “Gravity

with Gravitas: A Solution to the Border Puzzle.” American Economic Review 93, no. 1 (2003): 170192.

Berden, Koen, Joseph Francois, Martin Thelle, Paul Wymenga,

and Saara Tamminen. “Non-Tariff Measures in EU-US Trade and InvestmentAn

Economic Analysis.” Ecorys. Report for the European Commission, OJ 2007/S

180-219493, 2009. https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2009/december/tradoc_145613.pdf.

Borchert, Ingo, Batshur Gootiiz, and Aaditya Mattoo.

“Guide to the Services Trade Restrictions Database.” World Bank Policy Research

Working Paper WPS6108, 2012. https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2012/06/16441094/guide-services-trade-restrictions-database.

Dee, Philippa. “Services Trade Liberalisation in South

East European Countries.” Background Paper. Paris: OECD Publishing, January

2004.

Dihel, Nora, and Ben Shepherd. "Modal Estimates

of Services Barriers." OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 51. Paris: OECD

Publishing, 2007.

Fontagné, Lionel, Amélie Guillin, and Cristina

Mitaritonna. “Estimation of Tariff Equivalents for the Services Sectors.” CEPII

working paper No 201124, 2011.

Fontagné, Lionel, and Cristina Mitaritonna. “Assessing

Barriers to Trade in the Distribution and Telecom Sectors in Emerging

Countries.” World Trade Review 12,

no. 1 (2013): 5778. DOI:

10.1017/S1474745612000456.

Geloso Grosso, Massimo, Frédéric Gonzales, Sébastien

Miroudot, Hildegunn Kyvik Nordås, Dorothée Rouzet, and Asako Ueno.

"Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI): Scoring and Weighting

Methodology." OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 177. Paris: OECD Publishing,

2015.

Gooris, Julien, and Cristina Mitaritonna. “Which

Import Restrictions Matter for Trade in Services?” Working paper no. 2015-33.

Paris: CEPII research center, 2015.

Jafari, Yaghoob, and David G. Tarr. “Estimates of Ad

Valorem Equivalents of Barriers against Foreign Suppliers of Services in Eleven

Services Sectors and 103 Countries.” World

Economy, October 15, 2015. DOI: 10.1111/twec.12329.

Nordås, Hildegunn Kyvik, and Dorothée Rouzet.

"The Impact of Services Trade Restrictiveness on Trade Flows: First

Estimates." OECD Trade Policy Papers no. 178. Paris: OECD Publishing,

2015.

Park, S.C. “Measuring Tariff Equivalents in

Cross-Border Trade in Services.” Trade Working Papers no. 353. East Asian

Bureau of Economic Research, 2002.

Riker, David. “Estimates of the Impact of Restrictions

on Cross-Border Trade in Services.” U.S. International Trade Commission. Office

of Economics Research Note No. RN-2014-08A, 2014.

Van der Marel, Erik, and Ben Shepherd. “Services

Trade, Regulation and Regional Integration: Evidence from Sectoral Data.” World Economy 36, no. 11 (2013): 13931405.

Appendix

Table

A.1 Regional trade agreements: member listing

|

Dummy

|

Members

of the agreement

|

|

NAFTA

|

Canada, Mexico, United States

|

|

Europe

|

Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech

Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary,

Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland,

Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom

|

|

ASEAN

|

Brunei, Burma (Myanmar), Cambodia,

Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam

|

|

ANZCERTA

|

Australia, New Zealand

|